With every glance back at Number Four grinding up the slope, Brewman was more convinced that her water was foul. He chewed at his lip furiously. Blast Grint for not paying closer attention to the filling! Blast the Guild for leaving the tank at the North Cut three-quarters empty. Blast this shoddy coal - all he'd been able to secure at the last yard - which was boiling so slow. He looked out at the rising country around him and fixed each rowan and pine with an angry glare. Blast them!

But it was his own fault, and that was where the fury was sourced. He had known that Grint needed closer supervision. The man was fair enough for local runs, but on a trip like this he didn't have the sense to think further than the next milestone ahead. Steerbridge was laid up and Macklemore was taking the Beast down to Manchester with a four-car train. That job needed two good men, so young Horrocks had gone with him, leaving old Horrocks to handle the local work in Number Five for the time being. They were both well past their prime - old Horrocks could only really stand when clutching onto the regulator wheel and Five, well, she spat cinders whenever she was driven further than four mile.

And that had left only Grint and the boy to accompany him on this trip. He'd known he would need another hand for the stretch past Yarthwaite, and thank God, the man he'd taken on at the Crown didn't seem to be an idiot, but it was Grint, his own employee tasked with the responsibility of driving the second engine, that frustrated him. A steamsman needed more caution. The big engines were temperamental - Brewman wasn't ashamed of admitting that. They needed coaxing up the long slopes, warming gently in the morning, talking to, reading. Every gauge and valve told you their needs. Number Four had always been thirsty. It couldn't be called a fault, no. That would be a deeply ungrateful, even unfaithful thing to say about a steam-powered road locomotive. It was simply part of who she was. And a good driver took account.

It was a dirty tank, though. He hadn't filled at North Cut for years, but he should have known the water was going to be muddy. It was his own fault more

than Grint's.

"Mester Brewman," said the lad. "They's two engines a-coming up from the Cut."

Brewman turned about on the footplate and wiped the sweat out of his eyes. He could see the two dirty plumes of engines burning coal and accelerating up the road, clearly meaning to climb Hammer Hill the same evening as himself. He unclipped the monoscope from its mount above him and handed it to the boy.

"Take a good hard spy on 'em," he said. "Who is it?"

The boy peered away while Brewman concentrated on steering his own engine over the uneven road. The mighty Carocall locomotive didn't mind where she rolled, but the two wagons behind were piled right high, lashed tight over with canvas and cord, but still at risk. He let a little more steam in and immediately felt the pistons surge and the wheels pick up pace.

If it were a local firm, they'd have climbed the hill in the morning. So they were making the same run he was: up Hammer Hill by twilight, a rest at the filling station just over the crest and a run down into Finchwick in the morning. And probably on into the city after that...

"I think they's Guild engines, Mester," said the boy at last. "Red with gold bands."

"Hop back onto Number Four and look from there," growled Brewman. "Then light on up here as fast as you may. Go on - get!"

He'd stoke and drive for the next stretch. The hill didn't really steepen for another mile and Spadille, his own Number One engine, was singing and steaming as sweet as she ever did. It was Number Four that worried him, and he longed to coax her up the slope himself, but that would mean changing places with his man and he'd rather go blind than trust Grint to drive Spadille.

Brewman settled into his rhythm. Scoop and toss, scoop and toss, toe the door, look about, choose a line, check the pressure, feel the wheel. Scoop and toss, scoop and toss. Spadille was older than all of 'em, except Number Five, but she was tough. She was tough and she rode smooth and she never complained. She liked a hot fire and a long run and she lit quick again in the morning. A real steamsman's engine. His kind of engine. He allowed himself a grim smile and began to build the pressure a little more in anticipation of the climb.

The boy scrambled up again beside him. "Red and gold bands, Mester Brewman." He didn't have to say anymore. Brewman handed him the shovel and it was the boy's turn. Scoop and toss, scoop and toss, wiry muscles standing out through his thin cotton undershirt. Scoop and toss.

The boy knew not to ask questions, but Brewman liked him. Another three-four year and he could be of real use to Brewman and Son, Haulier. And if he were to drive, he needed to know the lay of the land.

"It's like this, son. We need water after the climb. Hammer Hill station has enough for both our engines, but maybe not for four. And the Guild fill first, see. Because it's their tank."

It hadn't always been their tank. Old Master Brewman had been one of the seven or eight hauliers who had seen it built, replacing the very unreliable roadside pool, but the Guild had bought it out more than ten year back. That rankled too. Because it was really Brewman's own water - at least in part.

"But we're going to be there first, Mester, ain't we? And they can't fill if we's already taken what we need."

"You think we'll be long ahead of 'em, Shawn boy?" The lad looked up into his master's face. He wasn't often called by his given name. He had hoped that the master liked him - he tried to be good - the tough, reliable roadsman he wanted to be. "You think we'll be filled at the rate Number Four is goin'?"

They looked back. The gap between their own rear wagon and the following locomotive had lengthened even since the boy had scurried between them. Brewman shook his head. He could see it all ahead of him. Half-filled, the Guild drivers would arrive upon him and claim their privilege. Four really needed a full flushing. He'd be stuck, waiting for the tank to refill at its trickle, until at least midday, or have to split his train of four wagons and take two on and deliver half the consignment. But he'd contracted to bring it in by the night of the eighteenth and the bounty wasn't a prize: it was his firm's lifeblood. They couldn't compete with the Guild's margins, so he had to get every delivery in on time. No penalties, no mishaps, no smirches on the Brewman name. That was the only way he had managed to keep the firm alive.The Highwayman Afloat

Why does Steam Highwayman feature a parallel, water-borne adventure? In Book 1, Smog and Ambuscade, around 150 passages out of the total 1017 are devoted to your options to take to the River Thames and captain your own steam barge, shipping freight and discovering unique adventures.

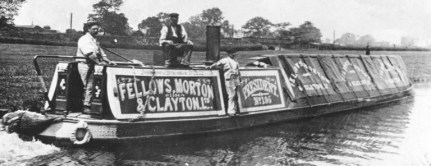

Because I love narrowboats. I love everything about them and their history, their lore, the short-lived and much-romaticised ‘traditional’ life of the bargee families. When I was designing my alternate but plausible steampunk past, I could not see how a Britain dependent upon steam power but lacking large railways (one of my premises) would work without some reference to the canal network at least. In out timeline, water-borne freight on the Thames has always remained competitive with the railways, and to some extent, the roads. Boats still lug building materials, hardcore, sewage and waste up and down the old river daily.

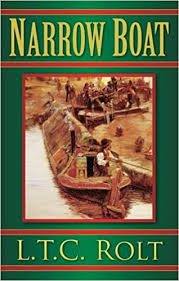

One of my regularly re-read books is LTC Rolt’s Narrow Boat. Essentially, he was the first canal tourist and also responsible for a lot of our modern romanticised view of the canals, but he was also a writer with a real interest in the genuine traditions of the canal people. I bought this some time back in 2010, I think, on a canal holiday with a good friend and his family.

When I lived in Marlow, between 2008 and 20012, I got to know the reach between Maidenhead and Henley very well. I had only been afloat on it a handful of times, but I was fascinated by the boathouses and bridges and could see how a highwayman adventuring back and forth across this great boundary would have to interact with its people and way of life. I had walked the towpath between Marlow and Henley in sun, rain and the dead of night.

Writing a continuation and development of the river into Book 2, Highways and Holloways, I’ve had to make some decisions. I’m currently trying to smooth out the reader’s journey to include fewer repetitions and more story. There should still be the opportunity to trade, investing relatively large amounts of capital to make good returns, all in the name of that retirement bank account at Coulters! After all, trading (and defeating pirates) by sea in Fabled Lands was always the best way to get your hands on a pile of cash.

But I know the reach between Henley and Oxford less well. So I’ll be depending on the good old OS171, Chris Cove-Smith’s The River Thames Book and lots of googlemaps. Nothing can replace the insight you gain from the locations themselves however and since a very large part of my pleasure in writing the Steam Highwayman series is to share my love of the parts of these parts of the world, I think I’ve got a good excuse to take an extended walk along the Thames pretty soon.

I still live by the Thames, but much further east and I see the Thames Barrier out of window and enjoy the tides defining the rhythm of the day. Regular shipments of estuary and Dogger-dredged aggregates are unloaded opposite our tower at Angerstein wharf – the largest gravel and sand unloading wharf of its kind Europe. The walks along the river here are quite different – and a good subject for another time, or another book.

Two other fluvial reads I’ll recommend here are the hilarious JK Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, which furnished me with the minimum of an amusing encounter in Smog and RL Stevenson’s An Inland Voyage. Three Men has still got plenty to give, so I’ll be mining it in the next fortnight, whereas the Stevenson is much more down-to-earth. I might borrow some of his cold and damp.

Skelwith Force

The torn polygonal scraps of slate that line

The torn polygonal scraps of slate that line

Brathay’s bed above the force

Are dull when plucked, laid out and dry, but shine

Under the crag-stream’s course.

The whole broad dale at Elter Water’s strewn

With spring’s flood-leavings

And the upturned ash and birch-tree ruin

Tell of unseen heavings.

Out of the hill came the water, stripping the stone,

And lushing up the dale,

Around the ice-old mounds, the under-bone

Of the sleeper of a forgotten tale.

The soft and hard are side by side and felt

By every walker strolling down to see

The water turn to steam,

The clear become opaque,

The straight begin to bend,

The sure become unsure,

At Skelwith Force, where glaciations melt

And obstacles sudden slip free.

Who is Josh Davidson? 3

Twenty years passed. And then, to follow our story, the BBC news ran a special report on a mystic who’d been living off handouts and and out of bins in Yorkshire. A beggar with a strange mysticism and an undeniable charisma who was starting to be followed.

Twenty years passed. And then, to follow our story, the BBC news ran a special report on a mystic who’d been living off handouts and and out of bins in Yorkshire. A beggar with a strange mysticism and an undeniable charisma who was starting to be followed.

Why anyone would want to follow this man was a mystery to the presenters. He seemed to have a completely negative message of a very old-fashioned, fire-and-brimstone type, but the makers of the programme noticed that such a message had been a cyclical part of British culture for hundreds of years, and this newer manifestation was simply a repeat of what had happened in the nineteenth, seventeenth and fifteenth centuries.

But it wasn’t simply a repeat. The man’s name was John Waters and he wasn’t so much a beggar or a tramp as a man who’d committed himself to a message. He’d been privately educated, raised in a wealthy home and in fact – not that anyone noticed – he was related, through his mother, to Moira Davidson. But this John Waters had dropped out and lived in the counter-culture, a hippy who still thought it was 1969 and that world harmony was around the corner.

He dressed from leftover and patched his own clothes, looking like a fool in motley from another age. His long beard was typically in a ponytail and his dreadlocks rivalled a senior rastafarian’s. Nobody could take such man seriously. He didn’t even wear shoes.

Yet when the Prime Minister came to Yorkshire, John Waters was somehow there, seen on camera, challenging him. When the new Archbishop was out surveying the church estates, John Waters managed to get through security and video of him lambasting the man went viral. “You’re a snake,” he’d said, toothily. “Looking for somewhere to hide? A nice flat stone to shelter under? You won’t escape. If you want to survive what’s coming, you need to change – you and all the church! You can’t simply say you believe in God! You’re a whole dead orchard without more than a few dried-up apples on branches that haven’t been pruned for years.”

The Archbishop’s reply was just as violent, but John Waters was suddenly headline news and people wanted to know more. He explained it all on video. “The washing ceremony is just to show that people want to change. That’s why they come to me and that’s why we do it. But that’s not the end of the story – because I’ve been told that we’re going to see someone with a real authority – someone who can wash with fire and God’s power and presence. And when he comes you won’t think I’m extreme.”

The Church of God had on official response. “God chose our people and this country thousands of years ago and it is the responsibility of our establishment and the government to maintain observance of God’s holy law. John Waters’ cries for change, although popular, in no way reflect the unchanging message of God for his people to obey the commandments and the traditions of our nation.” They believed he would disappear in time.

But John was right. He was carrying out his washing ceremony, as he called it, near Oxford on the banks of the Thames. Tens of thousands of people were there, being washed by John and his helpers – for he had quite a following by now, including a wealthy few who bankrolled him. And among the crowd, on a miserable Saturday in February, came a carpenter from Sheffield called Josh Davidson.

The whole thing was on film. People filming themselves, their friends going under, making promises to a new life. And you can find the clips were Josh Davidson’s turn comes in the queue. He’s been standing there in his work clothes, taken off his boots, clambers down the muddy broken-down slope of the cow-pasture and steps into the freezing water.

“What are you doing here?” asks John. “What have you got to change?”

Joshua said something, but no-one heard it.

“No,” said John. “You should wash me.”

“This is the right way,” said Joshua. And he turns and one of the videos shows the big smile on his face. He’s a typical looking guy with a bit of an accent – not strong, South Yorkshire, a beard, plaster-stained work overalls and up to his shins in muddy Thames water. “Look John, this is what was meant to happen.”

John relucantly agrees, shrugs and calls out to the crowd in harsh voice, tired by hours of calling in the drizzly late winter morning. “This man wants to change the way he lives! He will be made new, God promises!” And then he pushes him into the water and pulls him back out.

If you watch any of the videos, that’s the moment the conspiracy people go mad over. That moment when he came out. No-one can deny that Josh Davidson came out of the freezing February Thames near Oxford wet and smiling – a beautiful smile. But there’s plenty of people who will stand by all those who say they heard the voice of God shake the clouds and say something that really, if it’s true, everyone needs to know.

“This is my Son, and I love him, and I’m very happy with what he’s doing.”

Kon Tiki

Between the lines the story tells

I hear an author’s voice distinct.

Convinced that he and I are linked

I hope to set such stirring spells.

Adventure, or a sudden loss,

Alike speak truth when men can stand

And see themselves as earth of land

And venture futures on time’s toss.

The rafts of dreamers, mad or sane,

Carried by inhuman streams,

Rivers in the sea, strong beams

Of balsa wood and bamboo cane,

Light as light and fragile, lithe,

Barely count to city minds

But when the rocks and anchor grinds

Rafts pass swift on, serene and blithe.

For those who share the water-rolls,

Split and crash through frantic swells

A floating scrap of wood impels

No certain theory, proves no wholes,

But if you have become relaxed

And let the currents rise and dip

Allowed them lift you, turn and tip

Theories convince untaxed.

Lines from a Train Window by Bedford

By Bedford sheets of water blanket grooves –

The sillion silvered, overcome and smoothed.

Hedgerows prove ancestral farmers’ plans

But water came and drank up all the land.

A waste – lost value – blank diminished ground –

Or know that soil too needs rest and sleep.

A string of salmon-coloured floodlights from

A light industrial estate, those sheds

Near Wellingborough, parade a fan of rays

Across the fresh full mere like liquid stars.

Incoming Tide

Every pattern that’s made by the water

Where tides sculpt the ripples of low-slung sand levels

Is hidden, invisible, but for its traces,

The skeleton ridges and quartz-dancing revels.

Across the cold strand the sea is like silver,

Its lobes licking tenderly flattened out swells.

The sand barely rises, except when the water

Displays a true level and every tongue tells.

But even those waters are ebbing and rushing

And never the beach or the sea’s edge is smooth,

But climbing, high-rising, then falling, revealing,

It softens the crystals like lullabies soothe.

In Memoriam CRNM

I went alone by old canals

And saw the gardens grown from waste

Coal-heap compost, newspaper paste

And smelt the raindrops’ funerals.

Around a reedy, autumn pond

A wary grasp of sycamores

And mortal ash trees marked with flaws

Where wire fences scarred their bond.

Upon the puddles ripples ring;

The sky begins to decorate

The garden with a water-weight

And smack the mud, and patterns bring.

It is a partial sanctuary;

Aided and abetted, rich,

Leafmould rotting in a ditch,

A very sullen place to be.

The lonely walk I’ve taken here

Has led past corners where we laughed

And where we drank a loving draught

And where we shared a pint of beer.

How could it not, when every street

Has been a place we’ve known and shared?

When every roadsign once declared

The city was our place to meet?

I cannot walk past cranes or trees,

Follow paths or railway lines

Without seeing speaking signs

Of what you sometime meant to me.

I had to go to somewhere new –

A place I never shared, and still

As up the tower I found my thrill

I wanted so to be with you.

The train fled through a concrete scar

Half across the garden fields,

Through the chalk your bone-land yields

Not long away – and yet too far.

I felt my trespass in a place

Reserved for our shared wanderings.

I cried to think of happy things –

Cold on the downs, your true embrace.

The beach is shingle and I read

That half the land is shingle too,

Five centuries worth of land born new

Where once the sea lay in its bed.

Each stone a flint plucked from the chalk

And rounded by the waves’ rough play

Until it found a place to stay

Where rustles are the stonefalls’ talk.

There is a castle on the marsh

Built by a famous, frantic King,

Now a ruin, crumbling

And eaten – rotten – broken – harsh.

Built there to stand upon the shore

But stranded by the passing tides

Each bringing stones, and wrack besides.

The sea is not there anymore.

Two miles inland – what a plain sign

For all those things we deem most firm.

The world will change, so ends the term

Of all possession – but chiefly mine.

I loved you till it creased my soul;

I changed my mind to want your shape

And feel the lack when you’d escape:

You did. I let the pebbles roll.

So starts an avalanche again –

The smallest stones move rocks.

The freest hearts are bound with locks

That rust like links in anchor-chain.

Chalk at Broadstairs

When the tide, slow retreating from the beach north of Broadstairs,

Reveals all the liminal acres of shore,

A field of nobbly pinnacles rises

Slathered with purple, green-fingered, white-raw.

The chalk will feel greasy to fingertip gripping,

The seaweed is slippy beneath treading feet,

Yet the softest of stones is defeating the ocean

Absorbing the thunder where seas swell and meet.

The cliffs, yes they tumble, they fall and they shout,

Collapse in the surf of the tide’s furthest rush,

But ten days in twelve the water drains backward

And the roar of the ocean will turn into hush.

The power of water is soon dissipated,

Rollers and breakers split into rills

And the cliffs, slowly crumbling, must face the ocean

But twice a day water retreats and then stills.

Delabole Waterfall at High Tide

Upon the lip a flow like glass,

It seems as solid as the slate

Over which the waters mate,

Salt and sweet, where waves amass.

The waterfall persists its flow,

Its noisy rattle, chatter, rush

But the bigger water sweeps in hush

The shatters patterns with a throw.

Now synchronised in flow and draw

The waves ride in and mount the shelves

Some further, nearer, spend themselves

To salinate the pool-spread shore.

Is it a battle or a game?

These two waters meet head-on

Their distinct selves are seen, then gone.

And left, one cold and salt-sweet same.